Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive, attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

The 5 essential ingredients:

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question), worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here.

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions. If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic.

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic.

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title. Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

See how Grad Coach can help you.

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations. In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction. Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions:

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part, because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “research onion” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here.

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

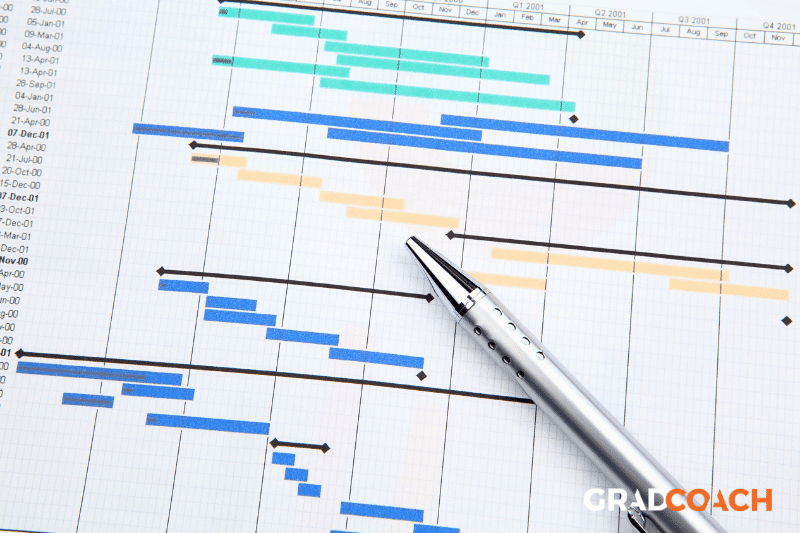

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management. In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog. If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template.

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp. If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this.